As a central cultural figure in New York City from the sixties to his death in 1987, visionary Andy Warhol wielded more artistic influence than even he knew. From A to B and back again, Michael A. Gonzales traces when pop met soul.

Raised in New York City during the seventies – perhaps the most perfect simulacrum of Planet Pop that America has to offer – at eight years old I was turned on to the wild world of Andy Warhol. Although I don’t remember where I first noticed the strange dude with his fright wig and glasses, Warhol’s image was seemingly everywhere. From television interviews to newspaper photos posed inside the hedonistic heaven of Studio 54 to advertisements for various products, most knew his pale face and monocyclic voice before they even saw his art.

Digging through art books at the Hamilton Grange library, I read about the “reptilian” (as David Bowie once described him), damn near albino artist ruling the art world from behind a silk-screening machine and snapping Polaroid pictures of celebrities, disco dancers and other strangers attempting to be famous for 15 minutes.

Dragged into the brilliant crimson of his infamous Campbell’s Soup cans, I became an instant fan of Warhol and the mythology surrounding the vibrant studio the Pittsburgh native called ‘The Factory’. An artistic utopia where the walls gleamed in aluminium foil, and the collective creative freaks gathered in various rooms reading movie magazines, digesting drugs, blaring rock music, writing poetry, publishing magazines and composing soundtracks as numerous super-8 projectors flickered boring black and white films in the background.

Although located in the most racially diverse city in America, the melting pot seemed to evaporate at The Factory’s entrance. Flipping through photos from the studio’s heyday in the sixties, The Factory, like most of the art world during that period, severely lacked racial diversity.

However, for many young kids of colour coming from various New York City hoods, Andy Warhol was the first ‘real’ artist, outside of Marvel Comics illustrators Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, whose work they recognised. Even though there were other ‘public’ artists like LeRoy Neiman and Peter Max, none were as cool and strange as Warhol.

“Back in the seventies, a lot of graff kids also went to local art high schools and were well aware of what was going on in modern art world and were down with Warhol,” Erik Talbert, an alumnus of the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan, explains. “I think the main reason his work resonated with the graff dudes was the colours that he used. Warhol’s pictures were always so vibrant.”

Many art critics believe Warhol’s paintings from the seventies were second rank, as though his surviving being shot in 1968 by crazy lady Valerie Solanas represented an artistic death instead. Nevertheless, for me, his celebrity portraiture period, especially the 1975 Mick Jagger series, were as sensational as jazz trumpeter Miles Davis going electric.

Having closed down The Factory after the shooting, it was during this period that Warhol began painting more black subjects including Muhammad Ali, OJ Simpson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. However, exploring the borders of race and class on Planet Pop, it was his exquisite portfolio of ten screen-printed portraits of glam African-American drag queens (Ladies and Gentlemen) from 1975 that are his most daring and inspired.

“New York has a thousand universes in it that don’t always connect,” writes Jay-Z in his 2010 quasi-autobiography Decoded, which features a 1984 Warhol ‘Rorschach’ painting on the cover. “But, we do all walk the same streets, see the same headlines in the Post, read the same writing on the walls. That shared landscape gets inside off all of us and, in some small way, unites us, and makes us think we know each other.”

For artist and hip-hop renaissance man Fred Brathwaite (aka Fab 5 Freddy) the artistic connection with Andy Warhol came when he was a kid living in the Bed-Stuy, once one of the most notorious ghettos in New York. “It was 1976 and I saw an Air France advertisement in a subway station,” Brathwaite recalls. “In the illustrated poster, there were various celebrities including Miles Davis, Carol Channing and Margaux Hemingway sitting on the airplane. In the back of the plane sitting alone was Andy Warhol. My first thought was, ‘Who is that guy with the crazy blonde hair and glasses?’”

While Fab 5 Freddy has had a fruitful career as a film producer (Wild Style), host of Yo! MTV Raps and video director (KRS-1, Gang Starr), his first love was always art. “Seeing Warhol’s startling image, I was curious, so I dug a little deeper and discovered how he set it off in the sixties art world. I can’t really say how many of the other graff kids I bombed with in Bed-Stuy knew of Warhol’s work, but for me he was cool, fun, interesting and radical.”

In 1980, four years after discovering Warhol’s work, Brathwaite painted an entire number 5 subway train in homage of the soup cans. “As an art nerd, I began feeling a real connection between graffiti and pop and I wanted to explore that in my own work.” The year before, he befriended another up-and-coming artist named Jean-Michel Basquiat, a young Puerto Rican and Haitian boho boy from Brooklyn who shared his passion for Warhol and later developed into a wild, styled artistic genius.

A few years later, after several chance meetings and finally a formal introduction, Warhol and Basquiat became friends. Not known for showing much emotion, Warhol was undoubtedly thrilled by Basquiat’s idol worship of both his paintings and persona as the two began hanging socially. Although Basquiat’s work was dubbed neo-expressionistic, one only has to gaze at the haunting paintings to see how much he was inspired by the pop landscape of music, comic books, films, television, cars and whatever else bleeped across his dreadlocked radar.

“For me, Basquiat’s work was mind-boggling,” says 40-year-old Los Angeles County Museum of Art curator Franklin Sirmans. “He might’ve been influenced by pop and Warhol, but Basquiat’s work elevated the whole sphere and discourse around visual arts.”

In addition to Basquiat’s prolific output, he styled and profiled at ritzy eateries Mr. Chow or The Odeon, often with Warhol and other downtown scenesters; wore beautiful Armani suits splashed with paint; and dated a pop tart who later became the Queen of Pop, Madonna. As Warhol had already shown, being pop was also about staying on your hustle and being seen on the scene.

In 1983, with young upstarts Julian Schnabel, Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf gaining on his fame, Warhol decided to collaborate with Basquiat at the suggestion of art dealer Bruno Bischofberger. “It was obvious that Warhol was holding on to Basquiat as though Jean-Michel was a life preserver,” laughs 36-year-old painter Jackson Brown. “At that point, Basquiat didn’t really need Warhol, but Warhol really needed him.”

Although adamant about not being influenced by Warhol, there is still much pop lustre in Brown’s portraits. “My father was a doorman at various ritzy buildings in New York City and I remember him bringing home a Sotheby’s catalogue that had reproductions of Warhol’s soup cans, Superman and Elvis,” he says. “I dug them at first, but then thought, ‘I could do that.’ For me, I revered Freddy’s graffiti version of the soup cans more, because they had more soul and passion. Warhol made being an artist look like the coolest thing on the planet, but I think his art is overrated.”

Basquiat by Jackson Brown (c) 2011

Unfortunately, when Warhol and Basquiat’s collaborations were unveiled in 1985 at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo, critics and fans held similar opinions. “I just didn’t understand the point of it all,” recalls graphic designer and artist Cey Adams, who attended the Mercer Street opening. “The paintings were entirely too big and they said nothing.”

Cey Adams and Bill Adler Hailing from Queens, Adams was a former graffiti writer and a pal of Keith Haring and Basquiat. In the early eighties, he was just another young black artist who admired Warhol’s collected works. Hired by fledgling hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons in 1984 as chief graphic designer for Def Jam Records and Rush Management, Adams designed album logos, tour merchandising and album/CD covers for LL Cool J, The Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, Slick Rick, Foxy Brown, Jay-Z, Method Man, DMX and others.

“The first time I met Warhol we were at a party for designer Willie Smith at the Limelight and the next time was at Keith Haring’s house,” Adams says. “His influence on me predates even my graff years, so standing next to him was like having a comic book hero in your living room. He didn’t talk much, but I asked him about Michael Jackson and we talked a little about his art. He was blunt and would just say what was on his mind. But, as popular as he was, I think he was amazed that young black kids knew who he was. To me, he was fascinating and mysterious.”

In the spring of 2011, Adams designed a poster for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibit Looking at Music 3.0, and is currently laying out the coffee table book Def Jam Recordings: The First 25 Years of the Last Great Record Label (Rizzoli International) edited by Bill Adler. “To this day, whether it’s a poster for Adidas or MoMA, or an album cover for Bad Boy [Records], that Warhol influence is a part of everything I do. The first thing I did when I started making money was buy two of his Muhammad Ali lithographs.”

After their 1985 show bombed, Basquiat began pulling away from Warhol, whom the critics accused of dictating too much power over their shared canvases. Although he rented a massive building from Warhol at 57 Great Jones Street, he saw little of his friend and instead began nodding out on the heroin slope. Two years later, Warhol passed away in 1987 after gall bladder surgery at the age of 58. The following year, Jean-Michel Basquiat overdosed and died in the bedroom of his Great Jones abode. He was 27.

More than two decades after their deaths, the art world is a vastly different cultural arena that includes more artists, curators and collectors of colour, as well as more women in roles of power. Today, Warhol and Basquiat are artistic icons whose paintings sell for millions while museum exhibits of their work travel throughout the world. In addition, their art has become hot status symbols collected by hip-hop superstars and executives including Jay-Z, Russell Simmons, Lyor Cohen and Swizz Beatz.

After spending 20 years away from the art, Fred Brathwaite returned to the studio and debuted his solo show New York: New Work at Gallery 151 in June 2010. The space was packed with guests that included hip-hop mogul P. Diddy, artist Lee Quinones, East Village scenester Shelia Jamison, rapper/producer Kanye West, filmmaker Charlie Ahearn, writer Nelson George and film producer Lisa Cortes.

Ironically, Brathwaite’s artistic rebirth was happening directly around the corner from where Jean-Michel Basquiet once lived and died. Standing in the gallery looking at Freddy’s stunning piece ‘Metro Movement’, an homage to his graffiti roots and Andy Warhol, behind me, a woman whispered, “Doesn’t this remind you of those days back in the eighties, going to openings at the Shafrazi Gallery.” Somewhere in pop heaven, Basquiat was smiling and Warhol was snapping a Polaroid.

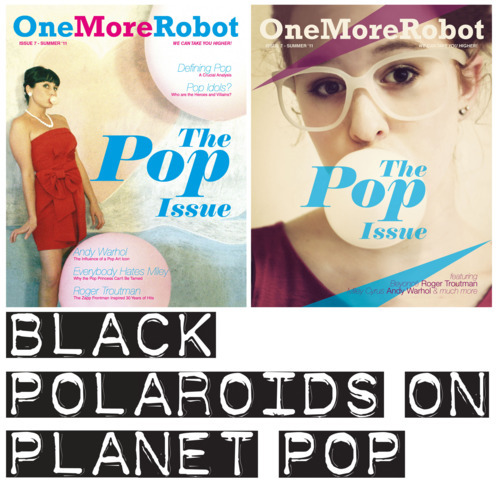

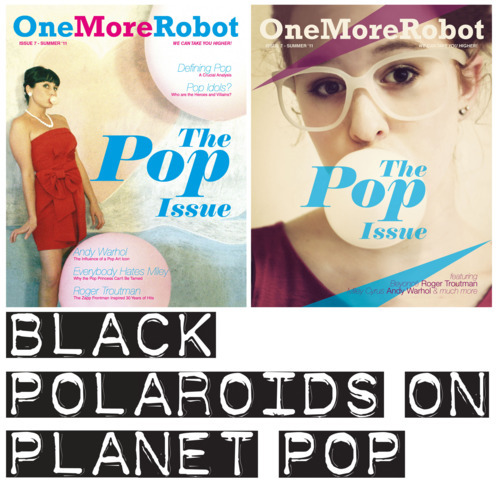

originally published in One More Robot #7

all images copyright (c) 2011 by the respective owners

http://www.onemorerobotmagazine.blogspot.com

Labels: Andy Warhol, Bill Adler, Cey Adams, Fab 5 Freddy, Jackson Brown, Jean-Michel Basquiat