After moving to Baltimore in the late-seventies, my mom dated a middle-aged be-bop fiend named Mr. Lee. Riding in his junky tan Cadillac that always reeked of second-hand smoke, I got my first lessons on the art of jazz. Steadily flicking ashes from a filterless cigarette, there was always a steady flow of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Billie Holiday or other old school jazzbos streaming from the speakers. “Now this is music,” Mr. Lee arrogantly assured me.

Flaunting his disdain against the David Bowie, Led Zeppelin and George Clinton albums that crowded my limited musical canon, Mr. Lee helped me to appreciate what I had secretly thought of as “strange noddling.” Later, hoping to impress him, I pulled out the closest thing to jazz in my collection, the stellar 1979 single “Street Life” by The Crusaders featuring vocalist Randy Crawford.

Spinning the 11:18 album version that I’d borrowed from my new best buddy Walter (dude had a basement full of dusty grooves), I was lost in the velvety textures of bandleader Joe Sample’s piano riffs and guest-vocalist Randy Crawford; years later, rappers Tupac and Masta Ace would sample this groove for their respective hip-hop hits.

As Mr. Lee listened to the entire track (in my young mind the jazzy soul conjured images of a cool neon wilderness populated with hop-heads, pool-hall hustlers and midnight cornerboys straight out of Nelson Algren), his face was blank. “That’s not jazz!” he bellowed. Storming out of the room, I overheard my mom wondering what had happened. “Nothing much, it’s just that boy of yours can’t tell pop music from real jazz.”

Though the Houston, Texas natives had originally called themselves the Jazz Crusaders, there were many purists who thought that these pioneering jazz/soul stylists represented the death of their beloved art. Yet, much like other fusionists in the post-Bitches Brew era of rhythmic rebellion, artists like Weather Report, Return to Forever and Herbie Hancock, the Crusaders were merely trying to forge their own musical identities in the often narrow minded jazz world. First formed in 1954 when pianist Joe Sample, tenor saxophonist Wilton Felder (who later doubled on electric bass) and drummer Stix Hooper were students at Phyllis Wheatley High School and played gigs under the names the Nite Hawks, Modern Jazz Sextet and Black Board Jungle Kids.

In an interview with writer Carina Prange, Sample recalled, “My father was a music lover. My older brother, he was 15 years older, played piano in an all black navy band in the Second World War. So he had records, records, records—every time he came home, he played the piano and I would just watch him. By six years, I told my mother I wanted to begin to play the piano and take piano lessons.”

According to jazz scholar Bob Blumenthal, “The music they played was typical of their hometown - bluesy, soulful, and spirited. They'd get together in the Fifth Ward, where Felder lived, to rehearse; before long, they fell sway to a new sound, by guys like Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach, whose records they'd listen to for hours.

“Adding trombonist Wayne Henderson, flutist/alto saxophonist Hubert Laws, and bass player Henry Wilson, they changed their name to the Modern Jazz Sextet and sought to master their instruments as the beboppers had done. But they never lost that Southern feel or their gulf basin roots. That group continued playing locally as the members worked their way through college.”

Moving to California in the early 1960s, after it was decided by the group that the New York City jazz scene had becoming too wily and weird as free jazz avant-gardists dominated the scene, they changed their name to the Jazz Crusaders. “The New York players made me realize that we were not jazz musicians,” Sample said years later. “We were territory musicians in love with all forms of African-American music.”

Recording throughout the sixties the Jazz Crusaders made eight albums for Pacific Jazz, where they were label-mates with Chet Baker and Chico Hamilton. Under the guidance of label owner/producer Richard Bock, the Jazz Crusaders released classic sides that included their 1961 debut Freedom Sounds (the title track, which opens this collection, was re-recorded in 1973) and Talk That Talk in 1966.

Yet, in an effort to expand their horizons like their musical brothers over at the progressive CTI Records, the Texas crew dropped the “Jazz” and jumped ship for MCA in 1971. On their first MCA disc simply titled 1, the Crusaders included a cover of Carole King’s pop ballad “So Far Away.”

In a review of 1, critic John Ballon wrote, “With their masterful improvising skills still in full force, the Crusaders plugged in, adding electric piano, electric bass, and most importantly, the electric guitar of Larry Carlton. Keeping their signature trombone & saxophone frontline of Wayne Henderson and Wilton Felder, the band really let loose.”

While some folks riff contentiously about the contributions of Sample and Carlton (whose hypnotic playing on “Scratch,” “Free As the Wind” and “Lilies of the Nile” is legendary), we should not allow there skills to overshadow the contributions of the groups co-creators Stix Hooper, Wayne Henderson and Wilton Felder. “Stix Hooper is perhaps one of the most underrated drummers in music,” says fusion aficionado Antonio Rodriguez. “He had a soulful musicality that other drummers couldn’t match. Stix was able to bridge blues and jazz, but he never sounded generic.”

Before “Street Life” became the Crusaders biggest crossover hit (the song has been used in neo-noir flicks

Sharkey’s Machine and

Jackie Brown), Wayne Henderson’s soulful “Keep That Same Old Feeling” from Those Southern Nights (1975) was the song most likely to be played simultaneously at Studio 54, a red-light basement party or a Harlem bar. With the group singing the lyrics themselves (later they would work with vocalists Bill Withers on “Soul Shadows” and Nancy Wilson on “The Way It Goes”), “Keep That Same Old Feeling” has the distinction of being the first Crusaders track with vocals.

Simply called “Trombone” by friends and collaborators (Henderson has worked with Bobby Womack, Joni Mitchell and Marvin Gaye) his contribution to the Crusaders includes their classic “Young Rabbits,” which was later used as the theme to the Academy Award-winning documentary When We Were Kings. Henderson also played drums on Hugh Masekela’s “Grazing in the Grass” and co-produced Rebbie Jackson’s “Centipede” (1984) along with her brother Michael.

The soulful saxophone and electric bass playing of Wilton Felder, a musician who has influenced a generation of players including Greg Osby and Nathan East, is undisputed. From the cool country grooves of “Way Back Home” (where Felder plays both instruments) to the wonderful “Nite Crawler” (which was written by Larry Carlton especially for Felder) to his session work (he played bass on the Jackson Five’s “I Want You Back”), Felder was a master.

“I remember the way each of us played and made our sound unique,” Felder told the Virginian-Pilot in 2006 while promoting his last solo disc

Let’s Spend Some Time. “There was individual playing within the context of a band. The Crusaders were a unit with each piece of the puzzle standing out.” Playing with one another, the puzzle was complete.

Labels: Jazz, Michael A. Gonzales, The Crusaders

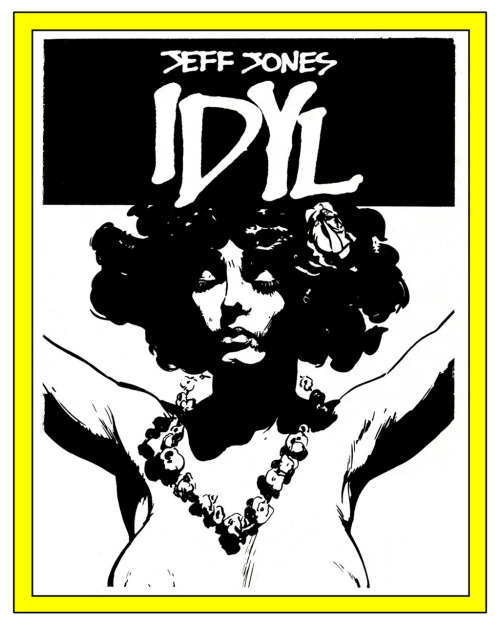

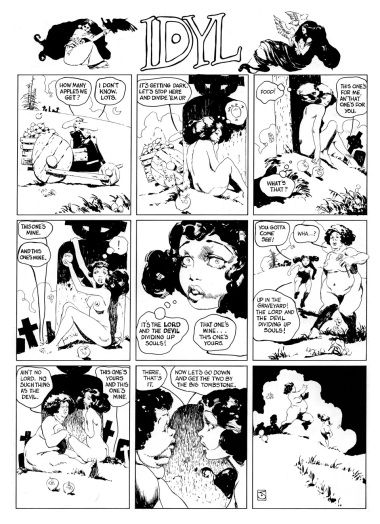

Like the visual equivalent of a Cocteau Twins album, the dreamy poetics of the late artist Jeff Jones one-page comic strip

Like the visual equivalent of a Cocteau Twins album, the dreamy poetics of the late artist Jeff Jones one-page comic strip  Unlike more commercial female comic book characters that pandered to the budding libidos of young male fans (i.e. Power Girl), the graceful beauty of Jones' creation was its innocence. The nakedness of the characters within their atmospheric landscape was as pure as Adam and Eve prior to eating that damn apple.

Unlike more commercial female comic book characters that pandered to the budding libidos of young male fans (i.e. Power Girl), the graceful beauty of Jones' creation was its innocence. The nakedness of the characters within their atmospheric landscape was as pure as Adam and Eve prior to eating that damn apple.

I never set out to become an erotica writer. In fact, prior to being commissioned by former Random House editor Carol Taylor (whose

I never set out to become an erotica writer. In fact, prior to being commissioned by former Random House editor Carol Taylor (whose

In the summer of 1985, I worked in the cassette department of Tower Records in New York City. A few months before, my girlfriend of a year told me at a birthday party that I threw for her, that she was sleeping with somebody else. Later, when I asked why she left me, she answered, “You’re too nice. I need somebody a little meaner.”

In the summer of 1985, I worked in the cassette department of Tower Records in New York City. A few months before, my girlfriend of a year told me at a birthday party that I threw for her, that she was sleeping with somebody else. Later, when I asked why she left me, she answered, “You’re too nice. I need somebody a little meaner.”