Such Sweet Thunder

Indroduction:

Under fiction editor SekouWrites, "Such Sweet Thunder" was first published in 2005 in Uptown magazine. This story, about gentrification in Harlem and the plight of small business owners, came to me one night while walking to the A train from the Studio Museum. As a Harlemnite who still visits my old block as well as my mom's former beautician Jackie (I spent so much time in that shop, Jackie's like an aunt to me) and my late stepfather's apartment building, it was shocking to see much the neighborhood had changed.

The real Shalimar barbershop, not to be confused with the fictional account below, used to be downstairs from daddy's apartment on 7th Avenue and 123rd Street. The last time I checked, about six months ago, the storefront was boarded up. Owned by the late Luther "Red" Randolph, it was also where daddy worked for years. This being the '60s, when men were into heavy duty marcelling, my mom has horror stories of how raw daddy's hands would be from conking hair all day.

In addition to my own Harlem nostalgia, I've always loved hanging out in barber shops, listening to men philosophize about everything from politics to women to who is the best MC. Recently I explained to a friend how, for me, barber shops were therapeutic; to this day, the buzz of clippers have a way of lulling me to that perfect place.

Last, but not least, I'd like to give a big shout out to my homie Duke Ellington, whose music, style and innovation has been a constant inspiration since I first heard "In a Sentimental Mood" when I was six. Presently, I'm trying to think of a good story so I can swap the title "Money Jungle."

Barber Shop by Jacob Lawerence

Barber Shop by Jacob LawerenceSuch Sweet Thunder

by Michael A. Gonzales

Pops from the barbershop knew the end of an era had arrived the moment he heard those dreadful diesels slithering down 7th Avenue. Lighting his first Marlboro that chilly April morning, his usually steady fingers trembled. Exhaling a whiff of smoke through thin lips, he sullenly glared out of the Shalimar’s dusty plate-glass window on its final day of business.

Two dirty fans swiftly whirled overhead, and the sweet scent of sizzling bacon drifted from Sara’s Luncheonette next door. Dressed in his usual uniform of a starched white shirt and black tie partially covered by a freshly laundered blue barber smock, Pops cracked his stiff neck.

In all of Pops’ years of looking out of that window, he had witnessed many neighborhood transformations: from ranting revolutionaries roaring about Malcolm X to soapbox preachers screaming about the souls of sinners; from nodding heroin junkies, their bugged eyes transfixed on the ground, to the panicky behavior of crack heads; from pretty little girls with Shirley Temple curls who would soon be mamas themselves to hard rock bad boys who grew up to be either pimps, punks or proper men.

A year ago, the neighborhood folks noticed a crew of white interlopers wearing yellow hard hats and carrying clipboards. The surveyors performed their jobs smugly, silently. Pointing at the storefronts, the men studied blueprints and jotted jumbled notes with sharpened pencils. With colored chalk, they scribbled peculiar symbols on the soiled sidewalks.

A few months later, much too their disdainful surprise, every merchant on the block received a formal letter from a newly formed city agency. Printed on raised lettered stationery, the memo informed the six store owners of plans to convert their aged shops into a sprawling shopping complex and luxury high-rises. In other words, as of April 29, 1999, Freddy’s Newsstand, Sara’s Luncheonette, Chino’s Sneakers, Fleishman’s Liquors, Vanessa’s number spot and the Shalimar Barbershop were to be closed forever.

Although Pops had lived in Harlem since he was twelve, one could still hear his Jamaican accent when he was angry. “God forbid we should try to take over one of their neighborhoods,” Pops protested the morning the official-looking letter arrived. “How many black boys done been beat down just walking through parts of Brooklyn or Staten Island? Harlem is my home. How they just gonna chase me out my home?”

As far as Pops could remember, he hadn’t been this vexed since M.L.K. had taken a bullet a year before the Shalimar opened. “At least then black folks were angry enough to riot,” he ranted. “These days we just take whatever slop we’re served.”

Black exhaust swirled from the hulking fleet of seven demolition vehicles skulking down the boulevard. Under an overcast sky the creeping convoy resembled a gloomy funeral procession. After months about anxious speculation of what would become of his friends and neighbors, the beast now roared outside their door.

The clamorous commotion of the Mack trucks caused the entire block to rumble. A few doors down, a demolition crew stridently demolished the two abandoned buildings on the corner. As ancient bricks crashed to the asphalt, Pops spotted a scraggly rat scurry beneath an emerald-hued El Dorado.

“Thirty years building a business and for what?” he huffed, extinguishing his cigarette. “Just to be kicked aside like trash in the name of progress.”

Pops slammed down his coffee mug on the stained Formica cabinet cluttered with sharpened scissors, sterile clippers, and plastic combs; on a shelf inside the cabinet was a white box overflowing with the multicolored candies he kept for kids. In the corner next to a chrome coat rack, Pops leaned his pure mahogany walking stick with its solid-gold handle. Handcrafted by an African dude down the block, Pops used the stick whenever his right leg cramped from standing too much.

Thirty years before, after Pops had served his adopted country in the Army, he had secured a veteran’s loan to open the Shalimar. The shop’s two other barber chairs were leased to his long time friends, a short spic named Carmelo and a former local soul singer everybody called Smokey.

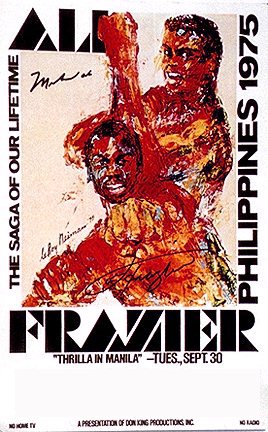

The Shalimar had a splintered window seat that was stacked with countless magazines while a multihued poster of Muhammad Ali painted by LeRoy Neiman hung on the urine yellow wall next to the green and gold Jamaican flag.

copyright 2010, LeRoy Neiman

copyright 2010, LeRoy NeimanUnderfoot, the cracked paisley patterned linoleum, with years of loose hairs trapped in its crevices, needed replacing, as did the dark blue hard plastic chairs that the customers used. While Carmelo and Smokey decorated their space between the mirrors with Jet magazine centerfolds, Pops had taped a radiant picture of his late wife Beverly to his section of the wall.

***

Opening the front door, a plump horsefly buzzed inside the barbershop and landed on the sugary rim of Pops’ coffee mug. He stepped onto the soiled sidewalk shaking his gray haired head in disbelief as a crazy lady with dirty fingernails fed the foul pigeons stale bread; she cooed along with the birds as though they shared a secret language.

“Her comes our new renaissance,” Freddy barked from his newsstand shed.

“This tearing down shit isn’t a renaissance,” Pops replied. He winced when a sharp pain shot up his leg. “More like a plague if you ask me. You seen how many rats been on this street since they started ripping down that building on the corner the other day?”

Surrounded by pulpy tabloids and slick magazines, Freddy stuck his bald dome out of the weather beaten stall. An unlit cigar dangled from his juicy lips. “Had to chase one out of my box this morning. Scared the hell out of me.” Looking closely at Pops, a concerned Freddy asked,

“How you holding up?”

“What can I say,” Pops’ said. “No matter how I feel it’s not gonna change nothing. Nothing at all.”

Violently coughing, Freddy spat into the dirty street. “Harlem is just another Plymouth Rock for these folks. Now I know how the damn Indians felt.”

Heartily, Pops laughed. “You ain’t said nothing slick to a can of oil, Freddy. Nothing at all. He strolled over to the newsstand and picked up a Daily News. Dropping two shiny quarters into Freddy’s tarnished tin tray, Pops strolled back inside.

Switching on the radio, Pops stopped turning the dial when he heard Duke Ellington’s melancholy music. “And that was ‘Star Crossed Lovers’, playing on the maestro’s 100th birthday,” the smoky voiced disc jockey said. “Next up comes Duke’s celestial ‘Come Sunday,’ featuring Mahalia Jackson.”

Still feeling an ache in his leg, Pop glanced at the walking stick. Carefully, he lowered the barber chair and plopped in the black leather seat. Opening his newspaper, he silently waited for the end to begin.

At dusk thunderclouds still hovered in the sky, but rain had yet to fall. Glancing at his tired face in the mirror, Pops touched his wrinkled forehead; a feverish heat rose beneath his fingers.

Like brown sugar, the babel of the barbershop bubbled: in the corner a rowdy quartet of regular hangout cats played a never ending game of spades. Turning up the radio a little bit, burly Smokey quietly hummed along to “Take the A Train” while sweeping hair from the floor.

“This gentrification jazz ain’t got a damn thing to do with race,” Carmelo proclaimed, his spic accent thick as stew. He was a short Rican, standing about five foot six in his colorful gators and black dress slacks. Sipping from a chilled bottle of Heineken as he cut a customer’s frizzy ‘fro. “This jazz is all about class.”

“Class?” Smokey replied. With his jungle of jeri curls, black velour sweatsuit, and thick gold chain, he looked like a broke down Barry White. “What a mida mida like you know about class.” Although they had been homeboys for years, Carmelo and Smokey loved to verbally spar.

“All I know is you’re like an old school house,” Carmelo said. “No class and no principals.” With the exception of Pops, the entire shop roared with laughter.

Pops opened the door and waited for a cool breeze to caress his warm face. Like floating quicksand, a murky mixture of dust and fumes hung in the air. Choking on the stale air, Pops felt a sudden tightness in his chest.

Taking a deep breath, the roar of the city sounded like a raucous big band grating on his nerves. Closing his eyes, Pops listened to the wail of the jittery jackhammers, the clank of cement mixers, the boom of bellowing voices. and the roar of restless machines.

“You all right over there, Pops,” Smokey asked. “You want some water or something?”

“I’ll be all right, just give me a minute. I need to get some air.” Reaching down, Pops shoved a plastic jam beneath the chrome-and-glass door.

“No disrespect, Pops,” Lester, one of the dudes playing cards in the back, said. At twenty-three, he was the youngest member of the barbershop crew. “But maybe you should look at this as a kind of blessing. Take some of that loot you done squirreled away and hop a flight to Miami Beach. Find yourself a big booty Cuban girl who keep you company.”

After Lester slapped five with his card playing cronies, Smokey barked, “Don’t go there, youngblood. Pops might not play the dozens, but I can get down.”

“I’m not trying to battle you, Smoke, I’m just sayin’...the ways of white folks is as old as the slave ships,” Lester snapped. “But, when the white man gets enough dough he spreads his wings and flies south. Chill in some condo, listen to Billie Holiday, sip some lemonade. Hell, who cares if they tear down every block in Harlem.”

Pops glared at Lester as through youngblood had just spat in his face.

“I care,” Pops hissed, his accent thick as fog.

“No disrespect Pops, but…”

“What do you know about Harlem anyway, boy?” Pops interrupted.

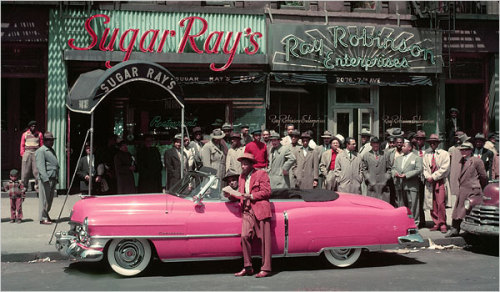

“What do you know about being a stranger in this city and making it home? What you know about Billy Eckstine crooning on stage at The Apollo on Saturday evening, drinking at Sugar Ray's that night or hearing Adam Clayton Powell Jr preaching at Abyssinian on Sunday morning? What you know about Bumpy Johnson or James Baldwin or Sammy Davis Jr. getting his hair clipped in my chair? Just because I’m old doesn’t mean I’m ready to lounge on the beach waiting for death.”

“Chill Pops,” Lester said, smiling uncomfortably. “Ain’t nobody say nothing ‘bout dying. I’m just saying...you don’t have to work forever.”

“Chill Pops,” Lester said, smiling uncomfortably. “Ain’t nobody say nothing ‘bout dying. I’m just saying...you don’t have to work forever.”“There’s nothing wrong with working,” Pops hissed. “It’s what men do.” A frigid wind blew through the open door; for a frozen minute, Pops’ words hung in the air. On the radio, the jazz jock cued-up Ellington’s “Such Sweet Thunder.”

Pops caught a glimpse of his face in the mirror. Glaring at his gray hair and wrinkled forehead, Pops wondered when he’d gotten so old. His flustered gaze fell to the floor the very moment a swollen sewer rat scampered through the open door.

“Jesus Christ!” Smokey screamed, dropping the broom.

Startled, the wide-eyed men stood up from their chairs as the long-tailed rat crashed into an overflowing wastebasket. Cigarette butts, used tissue, and various textures of hair tumbled to the floor. Pops stared at the repulsive rat scurrying across the soiled linoleum and slammed the front door. For a moment, the Shalimar was frozen in time.

Stiffly, Pops walked over to the corner and picked up the walking stick. In his fragile hands, the shellacked smoothness of the heavy mahogany contained the strength of a thousand tribes that once roamed the fertile motherlands of Ghana and Kenya and the Ivory Coast. In Pops’ perspiring hands, he felt the sweat of the mud colored men who had cultivated their kingdoms with callused fingers, sweaty brows and bloody feet, only to be eradicated by pale faces with loud machines.

Pops listened to the lush jazz streaming from the speakers, his tired eyes fixed on the vile vermin. He imagined himself as a swaggering young man coming of age in Harlem. Pops struggled to remember the first time he saw a buxom Beverly sitting on the stoop of her building. He pictured them, stylish young lovers in the summer of ‘65, sauntering through Sugar Hill.

A black prince on those once-vibrant streets, Pops walked the boulevards with an arrogance that everything he cherished in this world would last forever.

“Damn you,” Pops mumbled. “Damn you.” Outside, thunder crashed in the gloomy sky.

Afraid and confused, the rat stood on its hind legs and prepared to strike. Yet before it could leap, Pop savagely swung the walking stick and smashed the rodent’s skull. Blood and brains stained the yellow wall.

As he stared at the slaughtered rodent, Pops leg buckled and he collapsed to the cold floor. For the first time since the death of his beloved wife, tears fell from his eyes like rain.

Story copyright (c) 2010, Michael A. Gonzales

Images copyright (c) 2010 by respective creators

Labels: Crack Fiction, Duke Ellington, Fiction, Harlem Fiction, Jacob Lawrence, Michael A. Gonzales, Phyllis Sims, Such Sweet Thunder, The Shalimar

1 Comments:

Hi, Love your story.

Do you remember the Playboy Barber Shop in the 1960's?

Billy one of the barbers also worked the backstage door at the Apollo sometimes.

My husband Little Jimmy Scott's second wife was the only female barber at Shalimar in the 1950's. I have a photo from the newspaper of she, Jimmy, & Red.

Post a Comment

<< Home